How we do our work.

Introduction

Maternal Figures is a database of maternal health interventions implemented across Nigeria.

The goal of Maternal Figures is to document these interventions, with information about where they are located, how they are funded, and their successes and failures for journalists interested in reporting about maternal health in Nigeria.

The Maternal Figures database does not claim to be an exhaustive documentation of all of the maternal health interventions ever implemented in Nigeria. Also, for the interventions we have documented, Maternal Figures does not claim to have a complete picture of the intervention’s scope.

Maternal Figures is a collaborative project that is continuously evolving. By this, we mean that we are also looking to you to contribute to our database. Please contact us if there is an intervention you think we’re missing, you have access to a pivotal piece of information about an already documented intervention, or you want to include a link to a news story about an intervention.

This methodology explains our standards and procedures for collecting information about interventions and other details such as: how we define an intervention, how we found and documented each intervention,how we fact-checked each aspect of the intervention in order to present a substantial summary of its sources of funding, geographic location, and what the intervention hoped to achieve.

What is an intervention

Maternal Figures defines an intervention as a programme aimed at reducing maternal health whether nationally, in a specific state, local government area, or community. Our rationale for including a particular intervention in the database is that it shows long-term investment in the country or community, whether by the purpose of the intervention, or the amount of funding, time, and resources allocated to the cause.

There have been many attempts to reduce maternal mortality in Nigeria or at least highlight its devastating effects and root causes. But another important reason why we are particular about what counts as an intervention is because of how we hope the Maternal Figures database will be used. Ultimately, our goal is that Maternal Figures will serve as a tool for journalists to investigate the efficacy of maternal health interventions. We believe that it is just as important to report on the problem as it is to report on the proposed solutions.

As a result, we believe that programmes with established goals, funding sources, should be held accountable and the public has a right to know if they achieved what they set out to achieve.

Categories of an Intervention

-

Policy: government regulations focused on maternal health. These innovations could be a new agency to implement niche programmes, deployment of tools or manpower, but are initiated or facilitated by national or state governments.

-

Culture: community outreach or private stakeholder-led programmes focused on maternal health. These innovations highlight the creativity of the home population in determining their own future through the development of their own processes or procedures, or partnership with donor organizations.

Example: The Story Of Madadi: How An Act Of Courage Created A Unique Maternal Care Clinic In Kebbi

-

Technology: technology deployments focused on maternal health. While policy and cultural innovations tend to result in some technology being introduced, the prerequisite for innovations in this category is that they were developed deliberately for the population the solutions are deployed in.

Example: LifeBank: The Nigerian Startup Delivering Blood and Saving Lives via an App

-

Research: this is research that looks closely at factors that influence maternal health either nationally or in a specific state, local government area, or community. Our rationale is that not only does reputable maternal health research provide a solid foundation of expert sources for journalists, it is also a category that is funded by major development agencies like Canada’s International Development Research Centre.

-

Infrastructure: infrastructure includes programmes that range from mass training of health professionals to improvement of health facilities that will directly improve maternal health outcomes in the country, state, local government area, or community. These interventions are often found in budgets.

Example: Lagos Mother and Child Centre

-

Legislation: unlike policy, maternal health legislation serves to outlaw and restrict certain behaviors with the aim of protecting mothers. And unlike a policy, individuals who act in defiance of this law can be penalized.

Example: Fashola renews fight against child-maternal mortality

-

Other: other interventions often address all the facets of maternal deaths via the aforementioned categories or address tangential causes of maternal deaths like Malaria.

Example: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation Malaria in Pregnancy Project.

What is not an Intervention

It’s been easier for us to determine what is not an intervention than what is in some cases. During our research, we came across many well-intentioned programmes that have attempted to reduce maternal mortality. Some of these include one-off training programmes for health professionals or short-term advocacy programmes that rely primarily on notable personalities like actors or first ladies to promote maternal health awareness. Our refusal to include these projects in our database is not an indicator of their effectiveness, instead, it simply is a reflection of our initial definition of what an intervention is: something is singular about its goal to invest in the problem of maternal mortality in Nigeria and providing a long-term solution.

Other examples of programmes that Maternal Figures does not count as an intervention are:

- Pending legislative bills, like this Free Maternal Newborn and Child Health (FMNCH) in Kano which at the time this news story was published in 2018 was still pending in the state’s House of Assembly.

- Impactful, but indirect interventions like this one, which educates men and women about pregnancy and deliveries.

- International committees or working groups that include Nigeria, without an output of Nigeria’s local implementation or progress towards the common goal.

- Family planning or reproductive health programmes without a strong maternal health component. For major agencies like USAID, Maternal Health and Family Planning and Reproductive Health are funded as different health priorities.

- Programmes headed by the spouses of governors or presidents are laudable, but we don’t include them in the database because it’s often hard to track their impact after the term of the elected official is over.

- We don’t include all Corporate Social Responsibility Projects. We make exceptions for projects that have shown long-term investment in a community or have partnered with a government agency or local organization to execute.

- Short-term advocacy projects that rely heavily on ambassadors.

- Funding for general health infrastructure projects without a specific focus on maternal health as it is difficult to measure the full impact of these projects on maternal health.

Finding and Verifying Interventions

Like a puzzle, we matched information found from various sources to create a fuller picture of the interventions we documented. These included:

- News Stories

- Source documents from implementing organizations

- Annual Reports

- Project Databases

- Legislation

- Newspaper archives

- Surveys sent to journalists and recent nursing mothers

- Maternal Figures Questionnaire sent to implementing organizations

- Interviews conducted by Maternal Figures researchers

- Federal and State budgets

We scraped the websites of 18 publications (10 national newspapers, 1 archive, 7 foreign publications) for relevant coverage of maternal health interventions. We filtered through the list using headlines as a way to identify news stories and landed on 355 stories. We read through all 355 and included relevant stories to our database and In The News section. Sometimes news websites had been pulled down or articles had been lost. We relied on the All Africa database of news stories and the Wayback Machine when necessary.

We searched through USAID’s Development Exchange Clearinghouse, which is considered “the largest online resource for USAID-funded technical and programme documentation from more than 50 years of USAID's existence.” DEC is home to more than 155,000 documents available for viewing and electronic download. We searched the titles of relevant USAID funded projects in DEC and downloaded programme reports and other relevant documents. We also downloaded Nigeria’s country data from ForeignAssistance.gov, which aggregates all foreign assistance given to countries by the United States.

Implementing organizations like Women Health and Action Research Centre are registered non-profits in Nigeria so looked through all the annual reports we could find of implementing organizations that also happened to be non-profits. We also searched through the grant databases of non-profit funders like The Gates Foundation, Ford Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, TY Danjuma Foundation, MTN Foundation, and The GSM Association. We also went through databases for government aid agencies or financial institutions like The Department for International Development, Canada’s International Development Research Centre, and The World Bank. Agencies run by the Nigerian government were also a resource for us. We looked through the Nigeria Health Facility Registry and the Federal Ministry of Health Partners & Data Inventory.

When we learnt of a new intervention, we entered it into our Lead List - an Airtable base. This base had columns for each of the elements explained in the next section. As a baseline, each intervention required two independent sources to be verified. Once we had two sources, we looked for contact information and sent the information along to the main database also on Airtable. The website pulls and returns queries from this database.

Details of an Intervention

We have created a criteria of necessary information needed to mark an intervention as complete. This is a set of information we need to give users of the database enough context about the interventions. In this section, we go over all the elements.

Naming

Most times, we retain the interventions’ original name as listed by the implementing organization or funder. For example, well known projects like the Midwives Service Scheme are known as just that in our database. For interventions like free maternal and child health care programmes that are implemented differently across different states, we list each one as a separate intervention. So our database includes separate entries for the Enugu Free Maternal and Child Health Care programme and the Kano Free Maternal and Child Health Care programme. For some interventions, their naming either obscured the work they did or was confusingly similar to another intervention already in our database. In this case, we made slight modifications like including the name of the funder as a precursor to the intervention’s original name. An example is Society for Family Health’s ten-year Maternal and Child Health Care Project. In our database, we renamed the project as Society For Family Health Maternal And Child Health (MCH) Project Northeast Nigeria. For research interventions, we use the name on the academic or research paper.

Category

All interventions fall under one of the aforementioned categories. Some interventions fall under multiple categories. For example, NPHCDA’s Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Weeks (MNCHW) are considered both policy and culture interventions.

Summary, Location, and Status

Each intervention is summarized. Our summaries include their proposed impact, goals and achievements. For location, the intervention is situated in either a particular state, multiple states or nationally. Status is used to reflect the stage at which the intervention is at the time we entered it into the database. We recognize that the status of an intervention can change rapidly, so if you would like to register an update that is not reflected in our database, let us know.

In our database, an intervention may be listed as active, this means that at the time we included it in our database it was ongoing. An intervention may also be completed, which means that the intervention has run its course and ended on or after the proposed end date. Some interventions are listed as closed. Unlike completed, closed means that an intervention was ended prematurely for a number of reasons. Some of the interventions in our database that are considered as closed are often a result of a transition from one administration to another or a lack of funds. Stalled projects are projects where we were unable to verify continued activity.

Implementing Organization

Like the name suggests, implementing organizations are organizations that are in charge of implementing the interventions. These organizations can sometimes be the funders, but often they are not. For example, while USAID was the sole funder of the 1992 MotherCare Nigeria programme, John Snow International and the Federal Ministry of Health actually implemented the intervention by training health providers, educating women and improving health policy.

Tags

At our last count, we have over 50 tags. These tags are used to denote a programme’s stage, theme, funding or access. Through this we are able to identify what stage of maternal health the intervention address, the theme or category it uses, (service delivery, infrastructure, etc) what funding type the intervention benefits from - is it a loan from The World Bank or a grant from the MacArthur Foundation - and finally, how accessible it is to the women who need it. For example, is it a paid or free programme?

Funding

All information about programme funding is pulled from source documents we obtained from databases, budgets, news articles, etc. For example, funding amounts for DFID programmes are usually listed in the agency’s development tracker. Organisations like DFID often list programme budgets and actual amounts spent as separate items. For our purposes, we use the project’s actual spend for our Funding Received Till Date section. For programmes funded by different funding agencies with different currencies, we include both currencies and amounts in that section.

For programmes where funding came from disparate sources, we added up all the numbers made available in programme reports. For example, when documenting UNFPA’s Maternal Health Thematic Fund, we added up the programme’s expenditure for Nigeria from reports throughout the years. This is how we reached our funding amount received till date.

We continue to reiterate that our claims here are not exhaustive. So much money goes into these programmes and we made a point to document only what we could find. If you are aware of funding that we have not documented, please let us know by completing the feedback form within the intervention dropdown.

A good number of the interventions we’ve documented are multi-year, multi-funded, multi-country programmes that operate in Nigeria, our country of interest, but also in far-reaching countries like India, Burkina Faso, and Mexico.

Some of these interventions are funded by one agency, like the United States Agency for International Development and even when USAID makes a funding amount available, the amount is usually to implement the programme in all the countries where the intervention is active, not just Nigeria.

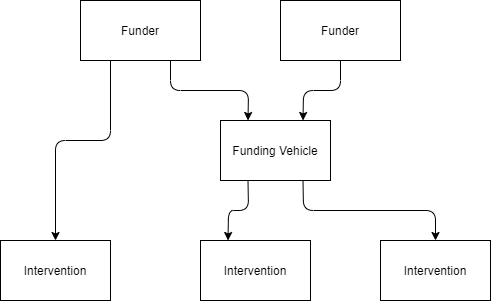

One example is the 10-year, $500 million MSD for Mothers global initiative According to the organization, they have reached over 9 million women in 48 countries around the world since 2011 by funding a diverse number of efforts to reduce maternal deaths. We have a number of interventions in our database that we know have benefited from this initiative, but it is unclear by exactly how much. As a result, we’ve created a category in our database for Funding Vehicles.

Funding Vehicles are used to identify large sums of money that have contributed to multiple interventions.

Funding Vehicles are not always multi-year, multi-funded, multi-country interventions. Sometimes they are national programmes like Nigeria’s Saving One Million Lives programme For Results initiative. SOML (Programme for Results) is financed by a $500million International Development Association (IDA) credit to the Federal Republic of Nigeria over a period of 4 years, but in addition other funders have contributed to it by providing grants for offshoot programmes. The financing amount is disbursed to Nigeria’s 36 states based on their ability to improve indicators like reducing maternal mortality and improving child nutrition.

Project ID

Project IDs are another way to identify an intervention. Different organizations use different combinations of numbers and letters to identify programmes. USAID programmes can usually be identified because they have a cooperative agreement number, while project IDs for DFID programmes begin with a GB.

Documents

When building the database, it was important that we verified the key facets of interventions as much as we could. Before we considered an intervention completely fact checked, we made sure that we had at least two sources verifying pertinent information like funding amounts and geographical locations. Some of these sources included news articles, or old pages on now defunct websites. (we relied on the Wayback Machine a fair bit) We would include these links in our own internal database to make sure we were always able to identify where we got a piece of information from. When we weren’t able to find information online, we used the maternal figures questionnaire as a source. Program managers for some implementing organizations were kind enough to fill these out and return them to us. All surveys can be found on SourceAfrica.net. In addition to completed surveys, we also included other source documents in our document cloud page. Almost every intervention has a link to a folder of attachments that can provide contextual information about the programme.

Contact Information

We pulled contact information from source documents or acquired them through our maternal figures questionnaire. All the numbers and emails that are on our website were publicly available.

Maternal Mortality Data

The dearth of maternal mortality data in Nigeria is a well known problem. In fact, we started Maternal Figures to counter it. Our project proposed to compare both qualitative and quantitative data side by side to see how maternal health interventions had affected the country’s maternal mortality ratio. We had great luck finding the qualitative data (the interventions) but very little luck finding the quantitative data (maternal mortality ratios, nationally and in states across the country)

Throughout our research we’ve been very open about the issues we’ve had. We’ve written about how different data sources say different things and we’ve even hosted training sessions with journalists to talk about how they can address this in their reporting.

For the purposes of our database, we relied on Nigeria’s Demographic Health Survey as a source for the country’s most recent maternal mortality ratio. Although the NDHS has been inconsistent in the past, we chose it because we were able to pair the 2018 national data released with the 2015 regional data released by the Federal Ministry of Health. We sourced these numbers from African Population Health Center’s Maternal Health in Nigeria report released in 2016.

Because we were unable to find recent state data, we paired state with regional data. For example, in our database, all states in the North West have the same regional maternal mortality ratio, 1026. Using data approved by the Federal Ministry of Health provides some kind of consistency despite the glaring gaps in state and national data. Also, both data sources were released in the last 5 years. (2018 for national data and 2015 for regional data)

We know that this is not an ideal solution. It is also not a permanent one and we plan to work with journalists and researchers to collect independent data. If you’re interested in working with us, please reach out to us.

Research Team

Researchers

Ashley Okwuosa is a Nigerian journalist currently based in Toronto. Her stories on immigration, education, and gender have been published in The Boston Globe, WNYC, Quartz, and more. She is a graduate of the Columbia Journalism School where she was a recipient of the African Pulitzer fellowship.

Chuma Asuzu is a researcher and engineer. On the team, he focuses on product management, data analysis and database organization. His writing focuses on technology in Africa and has appeared in Rest of World, OZY, and BusinessDay.

Research Affiliates

Patience Adejo is a Research Associate at EpiAfric and Programmes Coordinator at Nigeria Health Watch. She has a Bachelors in Technology in Library and Information Technology from the Federal University of Technology, Minna.

Aaliyah Ibrahim is a recent graduate of Yale University with a BSc in Biomedical Engineering and a Certificate in Human Rights. Her research interests coalesce around how health systems function to provide equitable access to health in the developing context.

Chisom Asuzu is a senior law student at the University of Ibadan. She has interned at a number of full service law firms and is writing her final thesis exploring emotional abuse against children in Nigeria.

Ifeanyi Agu is a full stack developer living in Toronto. He loves applying his development skills to make the world a better place by contributing to open source software.

Know an intervention that we haven’t listed?

The information contained on this website is for information purposes only. The information is provided from research conducted by Maternal Figures, and while we endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express, or implied.

Sign up for our newsletter to receive updates about our work and be the first to know when we update our database.